Wild foods – ideal superfoods for modern times

This is a short chapter in the book but it does get pretty technical and I deep dive into the biochemistry of nutrition and nutritional data.

However, the short answer to the question in the title is yes. By far.

And the more we look, the better we find them.

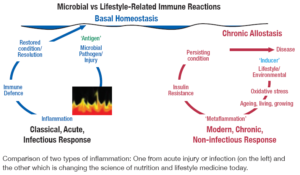

It might be obvious to us too, that as we embrace more farmed and processed foods, the worse our health becomes and the reasons are all in my book – from the challenges of our taste drives to the falling nutritional value of modern foods to lifestyle considerations. But the superior values of wild foods in quantity and quality are spectacular.

In summary, Indigenous Australians had from 2 to 10 times the number foods as the basis of their nutrition by comparison to us in the developed world. The range was determined by geography with the low end being in the deserts and the most foods available in the wet tropics of the North.

Additionally, these foods were from 6 to 50 times more nutritionally potent than our modern foods, when comparing any specific functional ingredient. If we had a single way of assessing antioxidant capacity, we could provide figures on the antioxidant capacity but in general terms, wild foods are staggeringly better for us that whatever we farm.

There are even some classes of antioxidants (for example, the fat soluble ones) that are entirely missing from conventional fruits yet are significant in wild foods.

Additionally, fructose and sucrose, or bad sugars are notably low in wild foods and even wild honey (sugarbag) from the tiny, stingless native bees is super-healthy in that the good sugars come in an amino acid cocktail along with enzymes, tannins, waxes and resins that give sugarbag its characteristic bitter-sweet profiles.

Store-bought honey is little more than a sugar hit and mainly bad sugars although if the honey is local and not imported (and therefore heated at 60°C for 24 hours to guard against chalk brood and other Italian bee diseases) you might find some enzymes and amino acids if the bees get to harvest bushland flowers and not just urban ornamental plants and other weeds.

Modern agriculture – hydroponics in the ground

The problem I explain in the book is that as we work to boost yields from plantations of food plants in order to reach what are economic levels from farmland, we need to move closer to what is effectively, hydroponics in the ground. This system of growing is familiar to anyone who has bought those root-bound punnets of salad greens and herbs and uses PVC pipes with holes for the punnets of vermiculite or other soil substitute into which the greens are sown. The pipes then get nutrient water circulated as the plants are fed whatever nutrients we think they need. The upshot is foods that are little more than ‘standing-up-water’. Salad greens with next to no nutritional value as foods but enough leaf to stop the watery tomatoes we slice onto our sandwiches from soaking the white slice bread. Herbs still manage to pump out enough aromatic ingredients to make them useful as flavour garnishes but again, the nutritional value is greatly diminished from the wild types of these herbs. The major reason for this is that to get the plants to grow fast and bushy, they are pumped with fertilizers and watered to produce the equivalent of our large, watery orbs of fruits and veg. Sure, there are some aromatics retained in the herbs but have you noticed how quickly they wilt and compared to the wild herbs from which they were bred, they are a shadow of their former selves.

Cropping of most of our vegetables is like this. Seeds are planted in paddocks that have been rendered microbially sterile with farm chemicals such as glyphosate and watered with regimes to pump up the plant’s size over growing seasons fueled by boosted nitrogen, potassium, urea and other fertilizer components. The huge watery blisters bear passing resemblance to the wild ancestors of these ‘new vegetables’ and their nutritional value is just as scant.

Farmers now grow wheat selections based on what is called a semi-dwarf variety developed in the USA. The reason for this is that as sterile soils are depleted of minerals, even silica is found lacking. Silica in micro-fine form is bound to flavonoids by plants and is a structural element in plants and our own cells, our hair, skin, nails and bones. The uptake of silica and subsequent bio-activation by plants is probably mediated by the micro-organisms killed by glyphosate.

Anyway. Semi-dwarf wheat with its shorter stalks, is less affected by the lack of silica in the wheat stalks as the heads of grain do not have to be held up as high as with normal wheat. Farmers get a crop but we are cheated with low silica grain. Luckily, we do get some silica from other sources of plants that are grown under more natural conditions.

Another reason to choose wild or near-wild food plants.

Wild Foods as World Record Holding Superfoods

The nutritional work I conducted in the 1980s and more by other researchers since then reveals some impressive facts: If we consider just a few of the antioxidants or the sum total antioxidant capacity of the three dozen or so species commercialized thus far, we find that the antioxidant values are from 6 to 50 times higher in wild foods than in conventional foods that are generally considered to be good sources of antioxidants. Blueberries are often used as a comparative food. Read more about this choice in the book as even blueberries are better for us if they are wild harvested and not cultivated.

And the Winner Is …

The front runner in terms of vitamin C capacity is still the Kakadu plum also known as the Kalari plum. These small, olive-sized, mucilaginous and fibre-filled fruits (drupes) can have over 50 times the ascorbic acid (vitamin C) content as the same weight of an orange of 40 years ago (when they actually had vitamin C). It has been estimated that 15% of the antioxidant capacity as measured by the ORAC assay comes from the vitamin C content and the remaining activity is due to other compounds. Additionally, the ORAC test accounts for not more than 27% of the total antioxidant capacity and other tests including the FRAP, TEAC, Folin–Ciocalteau and other methods. What this all means is that the 3 to 5% vitamin C level we published back in 1983 would suggest that the antioxidant capacity is huge.

A multitude of research publications over the last 10 years verify this massive value of a wide range of wild foods and the recommendation is simple – we need to eat more of them.

If you want an easy and convenient way to do this apart from foraging or sourcing near-wild foods, please visit this page on L.I.F.E. (Lyophilized Indigenous Food Essentials)™ and try it out for yourself.

In Wild Foods, I also address our mis-management of the environment; the consequences of falling biodiversity of resource; the challenge of global warming; and how we might feed ourselves in years to come.

In Wild Foods, I also address our mis-management of the environment; the consequences of falling biodiversity of resource; the challenge of global warming; and how we might feed ourselves in years to come.

I firmly believe that our continued survival, not just in Australia but on the planet, depends upon embracing a more wholistic paradigm. The Aboriginal management practices of land, population and resources and the nature of Australia’s wild foods themselves may determine if we continue to thrive as a species or we reach a point of singularity and everything changes. The year 1770 was such a point of singularity for the Tharawal of Botany Bay, followed closely by the Eora in and around Sydney. It would not be long before many lives and livelihoods would change for ever more or end in the process.

I firmly believe that our continued survival, not just in Australia but on the planet, depends upon embracing a more wholistic paradigm. The Aboriginal management practices of land, population and resources and the nature of Australia’s wild foods themselves may determine if we continue to thrive as a species or we reach a point of singularity and everything changes. The year 1770 was such a point of singularity for the Tharawal of Botany Bay, followed closely by the Eora in and around Sydney. It would not be long before many lives and livelihoods would change for ever more or end in the process.