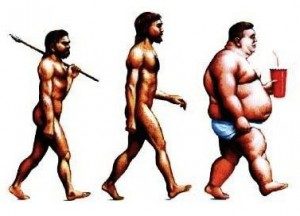

Traditional Aboriginal diets, their quality, diversity and supply, coupled with other lifestyle factors such as exercise, sleep and stress (or a lack of it), are an example of wholistic cures to the diseases of nutrition. And note that these same conditions were once called diseases of civilization, a term which was inappropriate to the world’s longest living civilization and which was devoid of these diseases.

I firmly believe that our continued survival, not just in Australia but on the planet, depends upon embracing a more wholistic paradigm. The Aboriginal management practices of land, population and resources and the nature of Australia’s wild foods themselves may determine if we continue to thrive as a species or we reach a point of singularity and everything changes. The year 1770 was such a point of singularity for the Tharawal of Botany Bay, followed closely by the Eora in and around Sydney. It would not be long before many lives and livelihoods would change for ever more or end in the process.

I firmly believe that our continued survival, not just in Australia but on the planet, depends upon embracing a more wholistic paradigm. The Aboriginal management practices of land, population and resources and the nature of Australia’s wild foods themselves may determine if we continue to thrive as a species or we reach a point of singularity and everything changes. The year 1770 was such a point of singularity for the Tharawal of Botany Bay, followed closely by the Eora in and around Sydney. It would not be long before many lives and livelihoods would change for ever more or end in the process.

However, many wild foods persisted despite the invading British and their land-clearing, river-damming and otherwise environmentally disruptive developments. I highly recommend delving into the world of John D.Lui of Regeneration International. He has said:

“If the intention of human society is to extract, to manufacture, to buy and sell things, then we are still going to have a lot of problems. But when we generate an understanding that the natural ecological functions that create air, water, food and energy are vastly more valuable than anything that has ever been produced or bought and sold, or anything that ever will be produced and bought and sold – this is the point where we turn the corner to a consciousness which is much more sustainable.

When humans work with nature, degraded landscapes can be restored in a matter of years, and economies can be regenerated, putting food security and climate change mitigation within our reach. In order to survive as a species, Liu explains, humanity must shift from commodifying nature to ‘naturalizing’ our economy.”

This chapter looks at the cautions we need to consider when out foraging or if choosing a wild food species to develop into a new mainstream food. I cover microbial threats, natural variation in chemical components in plants (chemovars), foraging pressure and sustainability concerns. If you think about it, the same sort of knowledge is needed if you were to forage freely in a supermarket yet avoid choosing the pet foods, soaps or garden chemicals as ingredients for your meal.

Ian Chivers from Native Seeds has a contribution to this chapter in a piece titled Splendour in the Grass in which he explores the potential future of wild grass seeds as foods.

Perhaps these might be guidelines for the wider naturalizing of our economy.